Piano trio, "Requiem for Our Lost Children," op. 63 (1943)

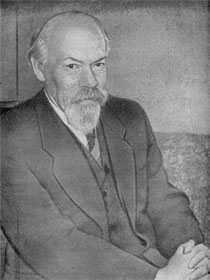

Mikhail Fabianovich Gnesin (1883-1957) was one of the leading Jewish musical voices to emerge in early twentieth-century Russia and went on to occupy a prominent place among the first generation of Soviet modernist composers.

Born in the city of Rostov-on-Don to a local rabbi, he came from a long line of Jewish musicians. His maternal grandfather, the itinerant Yiddish folksinger and synagogue chorister Shayke Fayfer (1802-1875), was a prominent fixture in the musical life of the city of Vilna (present-day Lithuania) for nearly six decades, while his mother was a talented pianist and vocalist and a student of the Polish composer Stanislaw Moniuszko (1819-1872).

Seven out of nine siblings went on to become famous as musicians or musical educators in Russian society. In 1895, five of Gnesin’s sisters established the Gnesin Musical Institute, a pioneering children’s music school that survives to the present as the prestigious high school division of the Moscow Conservatory.

Gnesin himself studied composition at the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he became Rimsky-Korsakov’s leading disciple. In 1908, he co-founded the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg, an organization that promoted the works of young Russian Jewish composers through concerts and publications. His own music mixed the late Romantic language of the Russian school with an interest in European modernism and Jewish folk music.

While he was associated with the early Russian avant-garde, composing song settings to many texts of Russian symbolist poets and futurist theater movement, he displayed a strong attachment to his Jewish cultural roots as well. From the 1920s to 1950s he taught at the Leningrad (formerly St. Petersburg) and Moscow conservatories, and wrote works on a variety of themes, including programmatic music on the Russian Revolution and folk musics of other Soviet nationalities. At the same time, he remained associated with Jewish cultural activities, even as late as the 1940s, yet managed to avoid political repression by Stalin.

His trio work was written in 1943 as the first news of the Nazi Holocaust was reaching the Soviet Union. The work’s title, “dedicated to the memory of our lost children,” was an oblique reference to the particular dimension of Jewish suffering. One of its notable performances came in June 1948, when the Polish National Radio broadcast the piece during a tribute to the fifth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a heroic last-ditch struggle of imprisoned Jews to defeat their Nazi captors.